Container Security & Developer Productivity with Cloud Native Buildpacks

Container Security & Developer Productivity

Context & Problems

The widespread adoption of Containerized workloads to be run on cloud platforms, has given rise to two interesting problems:

Developer Productivity

First, developers writing Dockerfiles (assuming Docker is the preferred container runtime), to deal with how their applications should be installed on the container OS image, along with what kind of dependencies are required. This takes away time from the developers when they could actually invest more time in developing and delivering business features. Furthermore, the developers are burdened by:

- having to understand what kind of a container OS image should be used for a base image

- how to organize the layers of the container image with their applications and dependencies

- having to understand and code a condusive environment including Networking for the application to operate within the container and in the external ecosystem

- ensure the container image that is created in the end conforms to full security policies as laid out by their organization

- periodically maintain/apply security patches and remediate vulnerabilities as dictated by the enterprise

- increase in counter-productive time for developers

Container Security

Second, the operators need to ensure proper OS Patches are propagated across all the VMs and containers as per security and compliance standards. But,

- with a large scale ecosystem with more than 100s or 1000s of containers with different container OS images makes it difficult to roll out the patches for maybe a CVE that is found

- operators need to work with developers across various teams in the enterprise to ensure the patches are rolled out in a timely manner

How do we mitigate these problems?

If we can take away the mundane and non-productive work of defining Dockerfiles from developers, thats a first step. But, who will define the containers? The answer is Cloud Native Buildpacks(CNB).

Buildpacks have been around for a few years now, and prominent platforms like Heroku and CloudFoundry use Buildpacks at their core for packaging and running apps. Cloud Native Buildpacks is a step further towards ensuring that the gap between operators and developers can be bridged. and make it easy for developers to containerize applications without writing Dockerfiles, and operators rolling out OS pactches to containers without needing to depend on developers.

Buildpacks primer

- Buildpacks provide a framework and runtime support for the applications.

- Buildpacks are able to detect what kind of application is it (Eg: Java/Spring, .NET, Node, Python, Ruby, etc)

- Buildpacks are can package the application with the required dependencies and runtime as needed

- Buildpacks can standardize the layouts for common application types like Java, Node, Python, etc.

- Buildpacks can be customized to enterprise needs if standardized buildpacks are not sufficient to the current needs

Now, there are a few things here that may not be relished by all. For example,

- The Buildpacks combine both the build and deploy phase. Esssentially, the buildpacks take your source code and turn them into a running application. This may not be ideal when we talk about testing changed before rolling out into higher environments.

- Deploying the same application multiple times, will build the whole application again and again, including all the layers. This is not super performing.

- Some platforms only use one base common image which brings in a lot of unnecessary dependencies which get bundled into the final application.

Some may argue that it’s better to use Dockerfile to have fine-grain control. But, with the growing needs of CI/CD automation, developers prefer to write multiple Dockerfiles to operate in each environment, and make use of Docker Compose to heavily customize the operating enviroment for Integration tests, etc.

Cloud Native Buildpacks (CNB)

While Dockerfiles definitely give fine grain control to developers, the customization needs definitely takes away precious time from developers when they can actually focus more on implementing business features along with tests. Also, more often container security takes a backseat when developers are heads down focused on getting the environment up and running asap. If the containers are indeed shipped to production, then it is just a ticking time-bomb for a security threat to go off.

Cloud Native Buildpacks solve this problem in an easy way. Let’s discuss this with an example.

I have a Spring Boot application that is a webapp. It looks like this:

Now, traditionally, if I wanted to containerize this application, I as a developer would just add a Dockerfile that looks like this:

FROM openjdk:8-jdk-alpine

RUN addgroup -S spring && adduser -S spring -G spring

USER spring:spring

ARG DEPENDENCY=build/dependency

COPY ${DEPENDENCY}/BOOT-INF/lib /app/lib

COPY ${DEPENDENCY}/META-INF /app/META-INF

COPY ${DEPENDENCY}/BOOT-INF/classes /app

ENTRYPOINT ["java","-cp","app:app/lib/*","ExampleApplication"]

To correctly package this app, and extract it with the right layout in order to be able to package it into the image, I would also add a Shell Script that looks like this:

#!/bin/sh

mkdir -p build/dependency && (cd build/dependency; jar -xf ../libs/*.jar)

docker build -t example-application:latest .

A few things to note here, I have taken utmost care in extracting my application and its dependencies to a suitable layout and copied them into the image. I have also used an openjdk alpine image as my base. In an enterprise, this might typically need to be vetted out for security vulnerabilities and certify that the image is hardened enough to use.

Now, the biggest problem is applying security patches to the container image or changing the base image as needed. Since the developer owns the Dockerfile, the operators need to depend on the developer to get this done.

Cloud Native buildpacks simplify this by taking away the need to write the actual Dockerfile. Let’s look at the steps to achieve this.

- Install the

packcli on your machine. FormacOS, usebrewto install as follows:

$ brew tap buildpack/tap

$ brew install pack

- In the project directory, where your maven/gradle files exists, run the following:

$ pack set-default-builder cloudfoundry/cnb:bionic

$ pack build <docker-registry-namespace>/<image-name>

The first command actually sets the builder to use to build the app. The builder has all the necessary buildpacks to be able to auto-detect and choose the best buildpack to be used. You can also run the following command to let pack suggest which builder to use:

$ pack suggest-builders

Suggested builders:

Cloud Foundry: cloudfoundry/cnb:bionic Ubuntu bionic base image with buildpacks for Java, NodeJS and Golang

Cloud Foundry: cloudfoundry/cnb:cflinuxfs3 cflinuxfs3 base image with buildpacks for Java, .NET, NodeJS, Golang, PHP, HTTPD and NGINX

Cloud Foundry: cloudfoundry/cnb:tiny Tiny base image (bionic build image, distroless run image) with buildpacks for Golang

Heroku: heroku/buildpacks:18 heroku-18 base image with buildpacks for Ruby, Java, Node.js, Python, Golang, & PHP

Tip: Learn more about a specific builder with:

pack inspect-builder [builder image]

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

gcr.io/paketo-buildpacks/run base-cnb 40845d52d6fb 7 days ago 71.2MB

cloudfoundry/cnb bionic 744709f7f5e0 40 years ago 764MB

example-app latest 0346e71fe9fd 40 years ago 260MB

You can see that two other images have also been downloaded, that were used to build the example-app image.

You can run this docker image as usual and/or push the image to your registry. Just use it like any other docker image.

When there is any application code change by a developer, CNB automatically reuses layers that are not affected, and only recreates the layers that are affected. This is not possible when writing a custom Dockerfile. That’s one of the biggest advantages because a developer need not worry about optimizing the image build process. With CNB, the subsequent build should be real quick.

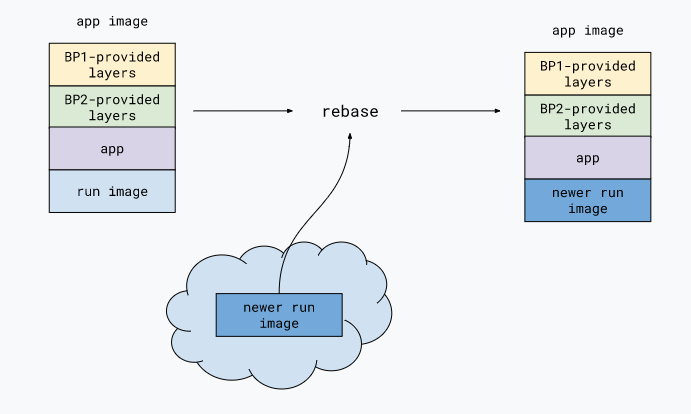

What happens if there is a CVE found in the base image cloudfoundry/cnb:bionic? How can an operate roll out the patch or updated base image without depending on a developer?

$ pack rebase <docker-registry-namespace>/<image-name> --publish

The above command would just check for a newer base run image, and download and swap that layer with the new one, from the original app image.

So, if this was integrated with a CI/CD pipeline, then it would save time greatly for developers, operators and make it very easy to handle container security in an enterprise setting.

We will discuss using KPack for automating the build and rollout process in the next blogpost. Also, I would discuss using Helm Charts for managing K8s deployments without having to write and manage numerous YAML files.